How Long Does It Take to Earn Out an Advance? My Sales Figures Revealed

Money Matters #2 - in which I share how many of MY books have earned out, and reveal their sales figures...

Welcome back to my Money Matters series, in which I take a deep dive into everything author earnings – and provide specific details of mine – in order to make the most opaque and mysterious area of publishing a little more transparent (hopefully!).

If you haven’t already, do read the previous post for the wider context to this series and a look at my advances, which will be useful for understanding today’s topic, which is all about…

EARNING OUT

Every author hopes to ‘earn out’ their advances, but what does that term actually mean?

Earning out explained

When an author signs a book contract with a publisher, the publisher pays them a sum of money upfront, known as an ‘advance’. Typically, for picture books, publishers will buy world rights for the full term of copyright.

Advances are typically split into three or four payments – often spanning several years – but are guaranteed, irrespective of future sales. In other words, even if their book sells zero copies, the author gets to keep their advance (providing that they’ve fulfilled the terms of their contract, of course).

Advances are, however, paid against future royalty earnings, hence the full term ‘advance on royalties’.

A royalty is a sum of money paid to the book’s creator(s) from each sale, at a rate specified in the publishing contract – usually as a percentage of the book’s RRP.

For instance, the typical royalty rate for a paperback picture book sold at the full RRP of £7.99 is 7.5%, split equally between the author and illustrator if they are not the same person, i.e. 3.75% for the author, 3.75% for the illustrator.

So, what ‘advance on royalties’ means in practice is that an author receives additional income from sales of their book ONLY once their pot of royalties exceeds the amount that they were paid for their advance.

And this is the point at which the author has ‘earned out’.

So how long does it take to earn out an advance? And what sort of sales figures are we talking?

This is very much a how-long-is-a-piece-of-string? type question, because the truth is that it varies wildly.

It’s also important to understand what the term ‘sales’ actually means in the context of advances, royalties and publishing contracts generally.

Whilst transactions through retailers’ tills are an important measure of a book’s (and author’s) success – it’s these that get reported to BookScan (the database that tracks books’ weekly trade retail sales), which provides information that publishers factor into their acquisitions decisions – ‘sales’ in this context is a bit more complicated.

Publishing operates on a sale-or-return basis, meaning that retailers reserve the right to return any unsold copies to the publisher.

So, really, sales = copies shipped by publisher to retailers – copies returned.

This sales-or-return model affects authors financially. Authors don’t earn royalties on returned copies. And because publishers must account for future returns, for at least the first few royalty periods, they reserve a percentage of an author’s earnings – adding to the time it takes the author to earn out their advance.

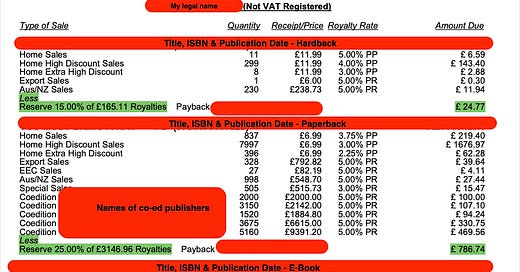

For example, here’s one of my royalty statements – heavily redacted; I’m fond of my job (and liberty) – in which you can see that, for this period, about £800 of earnings was reserved for future returns.

Not an insignificant proportion of my advance.

Anyway, the time/number of sales it takes for a book to earn out depends on many factors, including:

the size of the advance – the bigger the advance, the bigger the royalty pot to fill, and the bigger the number of sales needed to do so

the size of the print run – the initial number of copies printed and shipped to retailers may not be big enough to enable the author to earn out their advance, even if every single copy sells.

the return rate

the amount of marketing/publicity the publisher invests in the book – publishers can’t possibly promote each of their books equally, and with ludicrously high numbers of books released each year, the majority are destined to fly under the radar

timing, momentum, word-of-mouth and luck – factors that are all out of an author’s control, but which can have a considerable impact on sales

subsidiary/foreign rights sales – this last one’s A BIGGIE, so let’s consider it in detail…

A brief explanation of foreign rights sales

The Publisher’s Association Export Toolkit explains that ‘Foreign rights is the term given to the licensing of content to overseas publishers. Once in receipt of a licence overseas publishers are able to produce their own edition of the content for distribution in their market or territory.’

There are many forms of subsidiary rights, which include, but are not limited to:

translation rights

audio rights

film, TV and stage adaptation rights

merchandise rights

digital rights

On signing a contract, an author typically transfers some or all of their sub rights to the publisher, and the successful exploitation of subsidiary rights can prove lucrative for both.

Normally, an author’s income from the sale of sub rights is set against their advance. This means that they won’t receive any of this income until they’ve earned out their advance, but also that this income contributes towards earning out their advance – and more quickly.

If an upcoming publication garners huge interest, and lots of sub rights are sold pre-release, it’s possible for an author to earn out their advance before their book is even published.

I’ve no idea how frequently this happens in reality, though. It’s not happened to me. But the sale of the rights to my books to foreign publishers is the chief reason I’ve managed to earn out some of my advances.

Although there are many forms of subsidiary rights, translation rights are the most commonly sold for picture books (in my experience).

Translation rights are seemingly simple: when a publisher pays for translation rights, they buy the right to translate and publish an author’s book in another language – as one would expect.

But it’s not quite that simple, because there are two ways in which translation rights can be sold – and whilst both are good for an author, in financial terms, one is far better than the other, as you’ll see shortly from another of my royalty statements…

Translation deals v Co-edition deals

Typically, a Translation Rights deal is for a relatively short term – a few years, say – and is limited to a specific language and format, e.g. paperback rights in Korean.

It is usually a ‘royalty exclusive’ deal.

This means that the original publisher is paid an advance against royalties by the foreign publisher in exchange for the right to translate, print and sell the book in the foreign publisher’s territory.

The typical share given to the creator(s) for picture book Translation Rights is 75% – so if there’s an author and illustrator, they’ll each get 37.5%

A co-edition deal, whilst a form of translation right, is quite different.

In this instance, the original publisher prints the translated edition of the book on behalf of the foreign publisher, which supplies the text of the translation and any cover and copyright page changes.

The publishers negotiate sales of copies up front on a price per copy basis (e.g. 2000 copies at £2.30 per copy) which includes printing costs and also the author’s royalties – hence, co-edition deals are ‘royalty inclusive’ deals.

The typical share given to the creator(s) for co-edition rights deals is between 3% and 5% of the price received by the publishers.

In my experience, co-edition deals are more common than straight-up translation deals, particularly between European publishers.

However, when Translation Rights deals (where the author share is 75% or, in my case, 37.5%) are made, they can be lucrative and very helpful for earning out advances quickly; in my experience, they tend to be made with publishers in huge territories, such as the USA or China, where large volume sales (and, consequently, royalties) are likely.

The impact of rights sales on earning out an advance

As I mentioned above, the sale of rights to foreign publishers is the chief reason I’ve managed to earn out some of my advances (I’ll come on to how many in just a bit).

A look at one of my recent royalty statements should give you an indication of just how important foreign sales are to authors and their earnings, as well the financial advantage of Translation Rights deals when compared to co-edition deals.

The first page of this statement (which relates to a 6-month period) shows a few things:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Authorly Honest to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.